Recently, I posted a comment on Facebook about similarities I see between the current cancellations of concerts, film shootings, celebrity appearances, business transactions, etc., in anti-LGBTQ states and cancellations in the 1960s in response to racist segregation in Mississippi. I would like to explore the issue further and consider what we might apply from the past to our current situation. Making and exploring such comparisons can lead to dangerous rhetorical and historical simplifications. Michael Warner refers to such simplifications as a symptom of “Rainbow Theory,” a pluralism that often implies “a fantasized space where all embodied identities could be visibly represented as parallel forms of identity” (Warner 12). Making any comparison risks minimizing one or both moments in time, and risks homogenizing marginalized groups, as if their concerns and struggles are the same and can be easily compared. I do not consider African-American and LGBTQ parallel forms of identity. They are responses to different types of power, require different strategies for survival, and have different relationships with visibility and reprosexuality, the latter of which Warner defines as “a relation to self that finds its proper temporality and fulfillment in generational transmission” (Warner 9, 11-16). I am interested in the parallels found in the arguments for discrimination against both groups, hoping that a broader audience who may see clearly the flawed arguments in favor of racial segregation will be able to apply that recognition to the flawed arguments in favor of LGBTQ discrimination today. I write this from the perspective of a white, middle-aged, heterosexual woman, neither African American nor queer. This does not make my observations unimportant, but contextualizes them within my own experience and limited perspective. I will start with a look at 1960s segregation in Mississippi, then shift to current LGBTQ discrimination, making comparisons here and there that will allow for some conclusions for your consideration.

FIGHTING THE “SOVEREIGNTY COMMISSION” IN SEGREGATED 1960s MISSISSIPPI

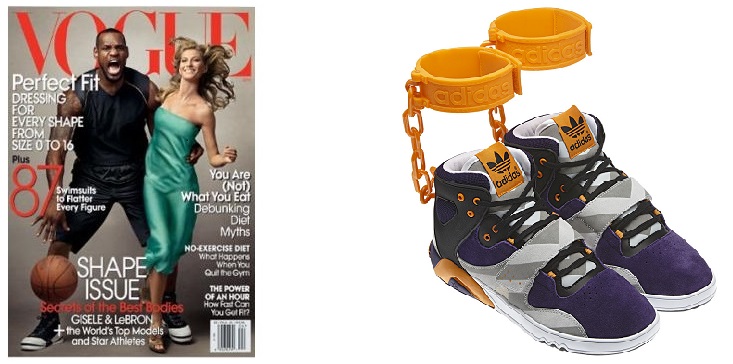

It is no secret that the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation did not end violent racism and discrimination against African Americans. Jim Crow laws and other segregationist practices re-enslaved African Americans, often leading to their arrest for infractions such as loitering, and punishment in the form of hard labor on farms or in mines. In addition, discriminatory lending practices and other forms of commercial-based racism prevented progress toward equality up to and beyond the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Mississippi was deeply entrenched in the battle for civil rights in part because so many of its white residents and politicians fought vehemently against equality and integration. One state organization tasked with maintaining the status quo through censorship and surveillance was the “Sovereignty Commission.” The stated aim of the commission was “’to protect the sovereignty of the State of Mississippi, and her sister states, from encroachment thereon by the Federal Government’.” Among other things, the Sovereignty Commission attempted to control media messages in and out of Mississippi so that they would be in line with “positive or ‘corrective’ portrayals of Mississippi,” which the commission considered “’the most lied about state in the Union’” (Classen 39). They provided “commission-written stories” and “advice to editors . . . on how to address and frame new civil rights events” and also omitted stories deemed out of step with Mississippi values (Classen 40). Black residents of Mississippi in the 1960s report that people were murdered for providing information from newspapers outside of the approved sources (Classen 75). Selling unapproved newspapers or magazines put you under harsh surveillance, and the Sovereignty Commission attempted to revoke the licenses of those selling newspapers critical of segregation (Classen 75, 79). According to Sam Bailey, who worked with Medgar Evers to fight for integration and to publish newspapers that revealed the truth about Mississippi, the local papers, controlled by the Sovereignty Commission, “weren’t going to print nothing unless you were accused of raping a white woman or killing a white. Then they would put you on the front page” (Classen 76). One step in the process of fighting segregation in the south involved alerting celebrities to discriminatory practices in the hopes that they would cancel appearances, bringing attention to government sanctioned racism and forcing segregated venues to refund ticket holders. The successful efforts of black student groups and civil rights organizations in Mississippi resulted in canceled appearances or performances by the stars of TV shows such as Bonanza, Hootenanny, and The Beverly Hillbillies, by musicians such as Al Hirt and Birgit Nilsson, and by NASA administrator James Webb.

RELIGIOUS AND SCIENTIFIC JUSTIFICATION FOR RACISM

White Americans have long justified the slavery of, discrimination against, and segregation of African Americans on religious and scientific grounds. In 1946, Mississippi Governor Theodore Bilbo wrote, “[p]urity of race is a gift of God … And God, in his infinite wisdom, has so ordained it that when man destroys his racial purity, it can never be redeemed.” Bilbo claimed his Christian God was the “original segregationist.” A 1959 court case in Virginia in which an interracial couple fought their arrest after they were married in another state and returned to Virginia was presided over by Judge Leon M. Bazile. When Judge Bazile sentenced the couple to one year in prison unless they agreed to leave the state for 25 years, he proclaimed, “Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents . . . The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix.” Bob Jones University, the South Carolina University that did not admit Black students until into the 1970s, and was denied IRS tax exempt status in the 1980s for its rules against interracial dating, rules that were only lifted in 2000, was named after Bob Jones, Sr., who, in his Easter 1960 sermon, said the following, quoting from the 26th verse of the 17th chapter of the Acts of the Apostles: “’And hath made of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth . . . ‘ But do not stop there, ‘. . . and hath determined the times before appointed, and the bounds of their habitation.’ Now, what does that say? That says that God Almighty fixed the bounds of their habitation. That is as clear as anything that was ever said.” He goes on to say that White Christians have always tried to help Black Christians in the southern states. Everything is fine, he says, with the exception of a few disturbances, but problems will continue in all nations that try to blur the lines their God intended to make between racial groups.

There have also been arguments providing scientific evidence for racial segregation. This is often referred to as “Scientific Racism,” and it was popular in and outside of the United States. Scientific Racism makes aporia-filled scientific claims about the inferiority or superiority of certain races, usually that the so-called white population is more advanced than the so-called black population. It provides the foundation for arguments made in criminology about race-based “tendencies” toward crime, and in eugenics about who should mate to produce a superior race. One’s African-ness, then, could be used as tautological evidence of degeneracy, both biological and psychological, just as one’s “white-ness” could be used as tautological evidence of being “honourable” and “square-dealing” (Dyer 65). This is also the foundation for claims that Black men have some immoral, innate drive to rape White women. The “real” concern, some white Americans would claim, was that segregation was essential for protecting their girls and women. Furthermore, Mississippians also felt their “cherished, distinctive way of life” threatened by “malevolent interlopers” (Classen 43, 94).

A BRIEF HISTORY OF RELIGIOUS FREEDOM LAWS

The current “religious freedom” laws in the U.S. claim to have their precedent in court decisions and acts signed into law in the 1990s. The first, in 1990, was a Supreme Court case in which the firing of two Oregon drug counselors was challenged, but upheld. The two counselors worked for a private drug rehabilitation organization, but participated in a religious ceremony at their Native American church that involved the ingestion of the hallucinogen peyote, illegal in Oregon. Justice Scalia saw allowing for such lawbreaking on religious grounds a slippery slope for which people could claim exemption from “civic obligations of almost every conceivable kind” for religious reasons. In 1993, President Clinton signed into law the “Religious Freedom Restoration Act,” which stated a government can “substantially burden” a person’s exercise of religion only if it advances an important government interest and does so in the least restrictive way possible. This instituted a test for the Supreme Court to levy against laws someone claimed restricted their religious beliefs and practices. The court would have to ask, “Does this law substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion?” and, if so, “Is this burden in the interest of advancing important government interest?” and, finally, “How can this government interest be upheld with the least restrictive burden on a person’s exercise of religion?” In 1997, the Supreme Court ruled that the Religious Freedom Restoration Act does not apply to states, so states started developing their own Religious Freedom Restoration Acts (RFRAs). 31 states have their own RFRAs. University of Virginia law professor Douglas Laycock explains, “The state court decisions interpreting their state constitutions arose in all sorts of contexts, mostly far removed from gay rights or same-sex marriage. There were cases about Amish buggies, hunting moose for native Alaskan funeral rituals, an attempt to take a church building by eminent domain, landmark laws that prohibited churches from modifying their buildings – all sorts of diverse conflicts between religious practice and pervasive regulation.”

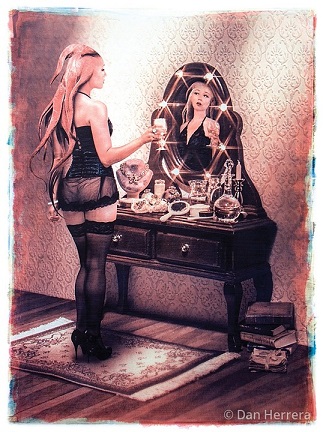

Current lawmakers were emboldened to apply RFRAs to LGBTQ discrimination by the 2014 Supreme Court decision that allowed Hobby Lobby and Conestoga Wood Specialties (a Mennonite-owned cabinet making company) to claim that the parts of the Affordable Care Act that cover contraception inhibit their religious beliefs and practices. Indiana governor Mike Pence cited this 2014 decision in support of his state’s 2015 RFRA law, which would count businesses and corporations as individuals who could also say a given law (like the federal law that opened marriage to all Americans in 2015) infringes on their religious freedom. After protests by companies and celebrities against the proposed Indiana law, Pence signed a revised version that prevents businesses from denying anyone services based on sexuality or gender identity. This brings us to today, when Mississippi, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Kansas are considering or have already passed legislation under the guise of “religious freedom” that will allow businesses or individuals to refuse service to the LGBTQ population. A 2015 executive order by Kansas governor Sam Brownback removes a previous order that protects state employees from discrimination based on gender identity or sexual orientation. Brownback explained that his action would “protect all Kansans without creating ‘protected classes’.” Mississippi governor Phil Bryant explains that his state’s RFRA will “’protect sincerely held religious beliefs and moral convictions of persons, organizations and private associations from discriminatory action by state government’.” North Carolina governor Pat McCrory supports Mississippi’s bill, which should be no surprise given McCrory’s support for his state’s “Public Facilities Privacy and Security Act“, which “bans individuals from using public bathrooms that do not correspond to their biological sex.” This act insists that users of multiple occupancy public restrooms must use the restroom that corresponds with the sex indicated on their birth certificate, and that although any board of education or public institution can provide single use or changing facilities, “in no event shall that accommodation result in the local boards of education allowing a student to use a multiple occupancy bathroom or changing facility . . . for a sex other than the student’s biological sex.” Recently, South Carolina also introduced a law requiring public bathroom use to correspond with biological sex. I cannot find specific language in the bills that explain how they will be enforced. Do residents need to start carrying around their birth certificate or state I.D.? Perhaps handmade calling cards will be necessary for individuals whose bodies will likely be read as opposite their biological sex, as in the case of Charlie Comero? It is also unclear how states allowing for discrimination against LGBTQ communities in the form of refusing services or employment will deal with the fact that the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission has interpreted section VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act to preclude LGBTQ discrimination and that the Supreme Court has already decided in favor of the rights of LGBTQ people in a number of cases. Celebrities and businesses ranging from Bruce Springsteen to Sharon Stone to PayPal to A+E Networks to 21st Century Fox to Nissan to John Grisham to Ringo Starr have canceled plans to work in the aforementioned states, signed petitions, made statements, or donated the money made during an appearance in an anti-LBGTQ state to an LBGTQ organization.

RELIGIOUS AND SCIENTIFIC JUSTIFICATION FOR LGBTQ DISCRIMINATION

The reasons provided for LBGT discrimination are varied, including those on the basis of religious and scientific grounds. The religious claims to allow for discrimination are based on the idea that a Christian business forced to provide service to a homosexual or transgender individual or couple impinges on that Christian business’s religious freedom. (As an important aside, although Christian groups, politicians, and individuals are the ones creating and enforcing and insisting on these laws, the laws apply to any religion that believes LGBTQ populations are sinful.) Addressing Christianity specifically, the biblical evidence against homosexuality is not particularly strong. The Old Testament Leviticus insists that a man who lies with a man as he is to lie with a woman should be stoned, but there is some debate within Christian communities regarding whether or not Jesus addressed LBGTQ populations, and even if he did it is still debated whether or not it is the place of Christians today to judge anyone. A great deal of concern is raised for “the children” to excuse LBGTQ bigotry and discrimination. Dr. Keith Ablow, a member of the Fox News Medical A-Team, encouraged his own readers/viewers to boycott the 2011 season of Dancing with the Stars because it featured Chaz Bono, in transition from female to male: “The last thing vulnerable children and adolescents need, as they wrestle with the normal process of establishing their identities, is to watch a captive crowd in a studio audience applaud on cue for someone whose search for an identity culminated with the removal of her breasts, the injection of steroids and, perhaps one day soon, the fashioning of a make-shift phallus to replace her vagina.” He insisted that we should “empathize” with Bono’s “gender dysphoria” and celebrate her achievements, but not support her decision to betray her biological sex. His attempts at empathy, already quite shaky, are obliterated when he makes a comparison to “someone who, tragically, believes that his species, rather than gender, is what is amiss and asks a plastic surgeon to build him a tail of flesh harvested from his abdomen.” If the echoes of 1960s segregation are not yet apparent, consider this similar claim: “they” will rape our girls/women. A group calling themselves “Campaign for Houston” made this argument and helped prevent anti-discrimination laws from passing in Houston, Texas. The group’s campaign was successful due to television ads such as the one containing this message: “No one is exempt. Even registered sex offenders could follow women or young girls into the bathroom. And if a business tried to stop them, they’d be fined. Protect women’s privacy. Prevent danger. Vote no on the Proposition 1 bathroom ordinance.” The group’s website describes itself in this way: “Campaign for Houston is made up of parents and family members who do not want their daughters, sisters or mothers forced to share restrooms in public facilities with gender-confused men, who – under this ordinance – can call themselves ‘women’ on a whim and use women’s restrooms whenever they wish.” They claim proponents of bills allowing individuals to use the restroom that corresponds with the gender with which they identify, intend to “make ‘sexual orientation’ and ‘gender identification’ two new protected classes.” These messages make a far too easy link between “sex offenders” and “gender-confused men,” not to mention they assume “gender-confused men” identify as women “on a whim,” and not after years and years of agonizing self-doubt. They transcribe what they see as scientific or psychological tendencies of transgender people into moral arguments about the safety of vulnerable cisgender populations. They assume that transgender individuals are the ones who should be feared, rather than the ones who are statistically, factually, and consistently the target of violent attacks, often for appearing to be in the wrong bathroom. The Houston group and others like it make assumptions about heterosexual cisgender men as well, who are seen as just one small step away from becoming a rapist. As if to make clear how easy it is for a heterosexual man to become a sexual predator, Mike Huckabee, former Arkansas governor and former U.S. Presidential candidate, confessed to a crowd at a 2015 National Broadcasters Convention, “’Now I wish that someone told me that when I was in high school that I could have felt like a woman when it came time to take showers in PE. I’m pretty sure that I would have found my feminine side and said, ‘Coach, I think I’d rather shower with the girls today’.’” Huckabee insisted that the new ordinances allowing bathroom choice based on self-identified gender were part of a “social experiment” in which children are “forced” to share bathrooms with “a 42-year-old man who feels more like a woman than he does a man.” Huckabee and other conservatives likely agree with the Campaign for Houston’s fears that allowing such LGBTQ freedoms is equivalent to “an attempt to re-structure society to fit a societal vision we simply do not share or can support.” Their cherished way of life is under attack.

MISPLACED FEAR AND THE THREAT OF “PROTECTED CLASSES”

Some parallels between 1960s segregation battles and the current efforts to discriminate LBGTQ discrimination have already emerged in my essay thus far. In Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates insists, “Race is the child of racism. Not the Father” (p. 7). Race is not some naturally occurring state that has been corrupted by racism, but was invented to categorize certain groups as inferior and others as superior. Race was born of racism. On a very broad level, the same could be said for sexuality and gender identity. All of these categories are discursive constructions. They were developed over time and employed to name and interpret groups of people. As Judith Butler has argued, not only gender, but sex, too, is constructed. The moment the concept of sex or gender enters discourse/language, which is a condition of its existence, it has social denotations/connotations (Butler 9-10). It is not, then, that sex is natural and gender is cultural. Instead, they are both named, socially meaningful, historically contingent terms and states that did not come before language. Gender and sex are unified in the performance of identity, and bodies are “always already a cultural sign” (Butler 90). Regardless of the scientific language used to describe a body part, that body part always signifies culturally, and that cultural signification is not separate from, but imbricated into scientific language. Discursive or social construction, however, does not make lived experience less physical, nor does it negate the meaningful difference between sex and gender for someone who is transitioning. This became powerfully apparent to me while teaching a class on women in art history. On the first day I asked my students to define “woman,” which eventually led us to discuss the categories “sex” and “gender.” I planned to carefully direct the students to the conclusion that there is little to no difference, and that they are both discursive constructions, but several students rightfully derailed my plans, pointing out the importance of being able to use those terms in different ways so that a transsexual or transgender person can identify as a gender different from their biological sex. My students insisted that the difference mattered even if the categories are each subject to considerations of cultural and temporal contexts. The difference matters not only because of the personal need to find the right combination, but also because of the constant threat of violence for those not looking, acting, talking, or performing in ways that are perfectly readable and legible according to prevailing social norms.

Since the advocates of anti-LGBTQ legislation so often express fears that their rights, their way of life, or their “daughters, sisters or mothers” will be violated, it seems reasonable to consider some statistics that reveal who has reason to be fearful. Violent crimes against members of the LGBTQ community have gone up in recent years, with 2015 seeing the highest rates yet. Tragically, these attacks and murders are sometimes at the hands of family members. In addition, a 2011 national survey revealed that “transgender people are four times more likely than the general population to report living in extreme poverty, making less than $10,000 per year, a standing that sometimes pushes them to enter the dangerous trade of sex work. Nearly 80% of transgender people report experiencing harassment at school when they were young. As adults, some report being physically assaulted [in] trains and buses, in retail stores and restaurants.” Meanwhile, states that have instituted laws that prevent discrimination and/or allow individuals to choose their restroom have had no increased reports of bathroom-related attacks or sexual assaults. The numbers have not gone up and there have been no reports of transgender abuse of such laws.

THE CIVIL RIGHTS OF PROTECTED CLASSES

Those who oppose changes our society has to make to “reduce the harassment regularly experienced by transgender people and others who don’t match people’s stereotypes of what it looks like to be a man or a woman” have turned to religion, science, and concerns for the safety of “daughters, sisters, and mothers” to cling desperately to a vision of the world as outdated as racially segregated bathrooms. The way of life that Mike Huckabee or Campaign for Houston or Keith Ablow have come to cherish will be somewhat altered by allowing transgender people to use the restroom that corresponds to their gender identity, just as it was for “most white Mississippians, as well as some black citizens, [who] believed the strict segregation of entertainment to be necessary and natural” (Classen, 87). LGBTQ individuals require protection because they have yet to receive the same rights and freedoms available to heterosexual cisgenders on a daily basis. This was also the case with African Americans when race became characteristic of a “protected class” legally shielded from discrimination. The federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act some U.S. governors consider the precedent for enacting discriminatory legislation can be used, somewhat ironically, against them: “Does this law substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion?” I don’t see how having to take photos at a gay wedding or allowing transgender individuals to choose the restroom they use does this, but let’s say yes in order to continue to the next question. “Is this burden in the interest of advancing important government interest?” Yes, in terms of preventing discrimination against what the EEOC has deemed a group worthy of protection against discrimination. “How can this government interest be upheld with the least restrictive burden on a person’s exercise of religion?” There is no biblical evidence that making a cake for a gay wedding, hiring someone even though they do not conform to standards that dictate how a “woman” should look and act, or letting someone choose the bathroom they use prevents someone from being Christian or practicing Christianity. I started this post thinking about two instances in which celebrities active in visual culture took a stand against discrimination, but some analysis has already been made on that topic, plus the lesson here is about recognizing a civil rights issue as a civil rights issue, and thinking carefully about what it means for a body to matter. The history of the category of the “human,” explains Judith Butler, “is not over, and the ‘human’ is not captured once and for all. That the category is crafted in time, and that it works through excluding a wide range of minorities means that its rearticulation will begin precisely at the point where the excluded speak to and from such a category” (Butler 13). The type of discrimination being written into law is far greater than a battle over bathrooms. At its core, it is a type of discrimination that attempts to put limits on “human.”